If misleading ‘free’ offers (i.e., offers at a zero-price but imposing non-monetary costs) are so widespread, are consumers skeptical when offered something for free? Is this mistrust so strong that consumers are willing to reject a truly beneficial deal which would help them earn more money? If so, can we design interventions that would help overcome this effect? I collaborated with Caroline Goukens from the Maastricht University School of Business and Economics and Vicki Morwitz from Columbia Business School to address these questions.

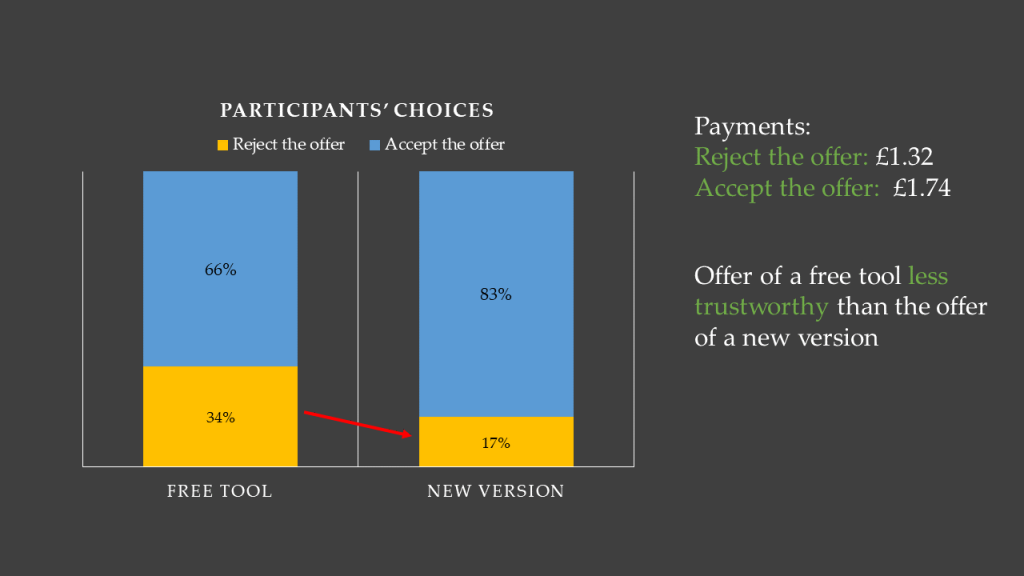

First, we wanted to test if people are more willing to reject a beneficial offer when it is called ‘free’ than when it is described in a more neutral way. To this end, we adapted our previous experiment on zero-price effect where participants solved matrices with ‘p’ and ‘b’ letters. In the experiment, participants first worked on this task in a trial round. Next, they were offered a tool which would help them solve more tasks correctly and, thus, earn more money. One group of participants saw this tool described as a ‘free’ tool. The other group was told that this is a new version of the task which they performed in the trial rounds. Participants in both groups were asked to choose whether they want to perform the task as in the trial rounds or with a free tool/in a new version. The results revealed that people are more likely to reject the offer when it is described as a ‘free’ tool than when it is described as a new version of a task.

In the second study, we wanted to test if this effect decreases once we force participants to think more carefully about their choice. We relied on the same design as in the first study. We only slightly changed the wording of the control offer. Now, some participants were deciding between doing the task as in the trial or using a free tool. Other participants decided between the task as in the trial or in an alternative version. Two other groups saw the same framing of the offer but they were asked to think carefully about their choice. They were also forced to spend at least a minute before making the decision. The results again showed more participants rejecting the offer when it is described as a free tool than when it is presented as an alternative version of the task. Instead of diminishing, this effect was even bigger in treatments where we asked participants to think carefully about their choice.

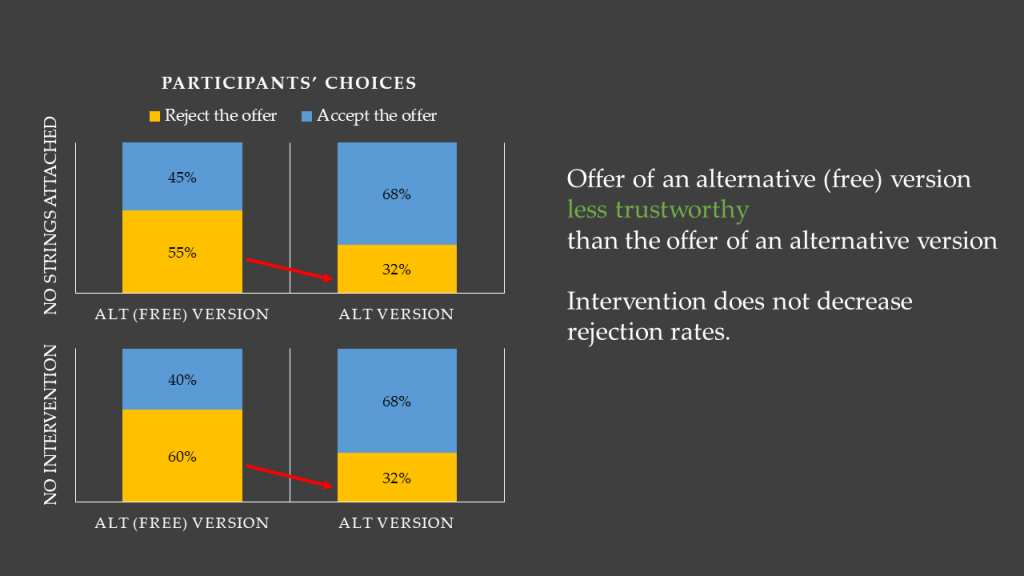

In the third study, we tested two additional framings and added an intervention. This time two groups were presented with an offer of either an alternative version of the task or an alternative (free) version of the task. The other two groups saw the same offers but were additionally informed that the offer comes with no strings attached. Again, participants were more likely to reject an offer when a word ‘free’ was mentioned. The offer of an alternative (free) version was also perceived as less trustworthy than the offer of an alternative version. The intervention, however, did not significantly decrease the rejection rates.

In Study 4, we tested another intervention. This time we let participants get familiar with the offeror. One group of participants took part in an unrelated neutral experiment on Day 1, the other group directly took part in an experiment similar to the one conducted in Study 2 in deliberate treatments, where some participants chose between doing the task as in the trial or in an alternative version while others decided between doing the task as in the trial or using a free tool. Participants were prompted to think carefully about their choice. On Day 2, the group that did an unrelated task on Day 1, was presented with our core experiment (an offer of a free tool or alternative task). The group that did our core task on Day 1, did an unrelated task on Day 2. We analyzed only observations of participants who completed the experiment on both days. The results showed that the intervention is ineffective. The percentage of participants rejecting an offer of a free tool remains the same whether they are familiar or unfamiliar with the offeror.

Finally, in Study 5 we tested another intervention. This time one group of participants that was either presented with a choice of an alternative version or a free tool saw Maastricht University logo in the upper right corner of the screen throughout the whole experiment (see picture below). The other group saw no logo on the screen.

The intervention was successful. Participants who saw the university logo on the screen were less likely to reject a free tool than participants who saw no logo.

The results are consistent throughout the five studies – people are more likely to reject an offer that mentions the word ‘free’ than a more neutral offer avoiding such a phrasing. These reactions seem to be driven by participants perceiving the ‘free’ offer as less trustworthy than the offer of an alternative/new task. Finally, only the intervention that makes salient a non-profit motivation of the offeror is successful in diminishing this effect.

All studies (hypotheses, design and planned analyses) were pre-registered on Open Science Framework. There, you can also find a program we used to collect data in Study 5 and Study 4.